When you are a kid you have those strange phobias that stalk you through your development and on into your teenage years. Weird fears that literally freeze you to the spot and turn your stomach upside down. You try to avoid the matter, whether it’s clowns, heights, wasps, or pigeons, and pretend to your mates that you don’t care, but really inside you’re shit scarred. For example, if you were afraid of swimming, you’d probably hang out by the pool pretending you are too cold to go for a dip and really need to read that last chapter, or would say that you’re going to come later to play waterfootball or that shit game your mates just “invented”, but you never come in the end - you keep making pathetic excuses.

As a kid all my fears were noise associated. While my brother was scared of rain, puppets and everything in general I was simply terrorised by fireworks and the sound of balloons popping, which didn’t make me a great guest at birthday parties. Actually, it wasn’t that much of a problem because I was half foreign and dressed in charity shop clothes, so the French middle class mums didn’t tend to invite me to their fancy “look at my kid’s dress” parties. It was a more of a problem, however, in Colombia where fireworks are illegal, so obviously the only thing you should do at a party, or any social occasion, is throw home-made bamboo fireworks all over the place. Horizontally, vertically, at the dog or the mother in law; it was my Vietnam.

I’m over it now, probably because I have lost a significant amount of my hearing form years of starring at people on stages without using “protection”. But there is an advantage to everything, being deaf doesn’t seem that bad. It didn’t stop Beethoven doing his day job well and Sir George Martin must have been going deaf when he decided to produce Celine Dion in the nineties, even though he did managed to do an OK job with Love (although his son was probably there to tell him what was going on). Everyone goes at least part deaf sooner or later, so what’s much more important in the senses department is sight, and thankfully it’s a bit harder to damage. You wouldn’t be a very good art critic if you couldn’t see, and although there are some great blind artists out there, what is really the point if you can’t see your own work? You have to rely on other people to tell you your work is not shit and they could just be humoring you. I’m sure someone once told Helen Keller she had a beautiful singing voice.

When I saw Willy Chyr‘s work on it’s Nice that over a month ago I was instantly curious about it. Willy creates gigantic sculptures entirely made of balloons and light. They are incredibly well made, complex, colourful and interesting. They have presence, an aura in the space they float around in helplessly. They are like flamboyant giant glofish, floating this way silently, although you know that they could pop at any second in a violent colourful explosion. The ephemeral nature of this sculptures also brings a mystic quality to them. They elude grasp and full understanding, to then dissolve into numerous pieces of flat and lifeless rubber.

Willy’s work is scientific based; he studied physics at university and this gives credibility to his work. The balloon creatures he makes could easily be reproductions of deep sea species.

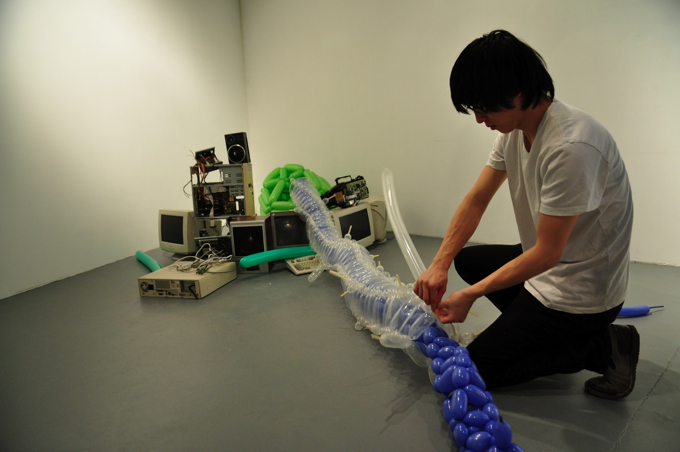

We asked Wily to answer some of our questions and he kindly obliged. He also sent some pictures of his studio in Chicago.

Introduce yourself.

My name is Willy Chyr. I’m a sculptor working primarily with balloons and light. I live in Chicago.

Describe us your work.

My sculptures are inspired by various entities and phenomena in nature, and the scientific principles that govern them. My pieces are constructed entirely out of balloons (the same ones used for twisting balloon animals), and are sometimes embedded with LEDs and other electronics to mimic biological behaviour.

The first series of sculptures I created were inspired by bioluminescence - the emission of light by living organisms. The sculptures contained within them a network of LEDs controlled by a small microchip to light up in different patterns.

You studied Physics and Economics. How did you end up being a balloon artist? Do you ever consider going back to a more conventional profession in economics and working in an office as a banker, or an accountant?

I learned to juggle while in college and started performing with a small local circus. We would get invited to perform at various events around Chicago, and one time, the event organizers were looking for a balloon artist. I didn’t know anything about balloons, but the pay was pretty good, especially for a student, so I signed up for the gig and learned to make balloon animals. After that, I was the go-to balloon guy.

At the same time, I was working in various laboratories as a research assistant. In fact, I spent the summer after my third year of college working for the National Institute of Nuclear Physics in Italy. When I returned to Chicago, I started looking for a way to combine my scientific work with the circus arts and this led me to the idea of creating large balloon sculptures inspired by different things I learned in science.

I’ve never really thought about working as a banker or an accountant. I do sometimes think about going back to physics or working as an engineer.

How do people react when you tell them about your work?

When I tell people I make balloon sculptures they usually think I’m talking about little balloon puppies and swords that you see at birthday parties. I did do those for a while, but not anymore. Sometimes people ask me if I’m a clown (I’m not, in case you were wondering). It’s hard to describe my work because most people haven’t seen anything like it, so I usually just show them pictures of my stuff, and then the response is usually pretty positive.

What did you wanted to be as a kid? Did you have a particular interest in the circus? Were you ever scared of balloons popping?

I never really thought about going into the arts as a kid. Originally, I wanted to be a doctor and for a while I thought about becoming an academic. However, I’ve always been very fascinated by the circus. I love how over-the-top everything is and it’s also very interesting to see how the circus has evolved. The contemporary troupes are obviously very different from the old ones, but our perceptions of the circus have also changed a lot.

I don’t remember ever being scared of balloons popping.

How long do your sculptures lasts? How do you feel about the ephemeral nature of your work?

The sculptures last about 3 to 4 weeks. I used to wish my pieces could last longer, but I’ve learned to really like the ephemeral nature of the sculptures. It definitely gives me much more flexibility with regards to the kinds of space in which I can set up my installations. For example, a lot of places where I install my work are not typical exhibition spaces, where people would be reluctant to set up something permanent, but a temporary installation that lasts 3 weeks is just perfect.

The fact that the balloons deflate overtime also adds another dimension to the work, because it’s always changing, albeit very slightly. You can install a piece and then look at it two weeks later and it will be very different. Sometimes, I feel the sculpture is not “ripe” until at least a week or two after it has been installed. I’d like to think of each piece as going through a certain life cycle - birth, maturity, and death.

What inspires you? Are you interested in other art disciplines?

Nature is a constant source of inspiration for me. I am also a big fan of science fiction and I think that comes out a bit in my work. I try to keep up with a lot of developments in technology, especially a lot of the open-source projects out there, because sometimes I will get ideas on how to incorporate that technology into my sculptures, or discover a better way to do something.

I am very interested in film and animation. I just finished a short stop-motion animation about two dinosaurs and I am actually now working on the storyboard for another short film. I switch back and forth between the sculptures and animations when I work, because I feel they are using different parts of my brain and pushing me in different ways.

How long does it take you to form a piece like The Comb Jelly? What is your working process?

The Comb Jelly took a pretty long time to build – a total of 3 days with a team of 6 people. However, that’s mainly because it was the first large piece I ever built and a lot of time was spent just trying to figure out how to do things.

I didn’t have any experience working with balloons on such a large scale before The Comb Jelly, and I also didn’t know much about electronics prior to doing the piece, much less how to incorporate electronics with balloons. We were also using a manual pump to inflate the balloons, so that slowed the process down quite a bit.

Nowadays, I use an electric pump, and can create a sculpture by myself in about one or two days. I would say on average it takes about 15 – 20 hours to build a piece. Usually, I’ll get an idea for a new sculpture, and I’ll let that idea develop for a week or so in my head, and then do a couple of sketches to work out the details, such as the exact size and how I am going to install it.

What are the specifications of creating balloons sculptures? Do they need to be kept at a certain temperature? Is it better to inflate them with a machine or by blowing them up yourself?

You don’t really need to take special care of balloon sculptures. Generally, balloons deflate slightly faster when they are under direct sunlight, but I haven’t found the difference to be very significant.

It is definitely much better to inflate balloons with a machine. I used to use a manual floor pump to blow up the balloons, but that gets pretty exhausting when you’re blowing up hundred of them at a time. The electric pump has been a real time/energy saver.

Do you live from your art?

Nope. Currently, I am an artist-in-residence at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts in Omaha, Nebraska, and so I get to spend all my time working on my art. Normally though, I have a day job in Chicago.

What would be an ideal commission for you? Where would you like to see your work?

The ideal commission would be creating a series of installations for an aquarium. I can’t imagine a more appropriate or ideal setting for the sculptures, especially since the first pieces I did were inspired by marine bioluminescent creatures.

Can you make an auto-portrait for us?

Yes.

Thank you Willy.